Captain, Flt. Lt. Pat McNulty, DFC, RAAF

Pilot Instructor: Flt. Lt. John Spiller, DFC, RAF. The link will download a pdf which includes an image of Flt. Lt. Spiller.

Copilot, Flying Officer Frank Doak, RAAF

Flying Officer Noel P. Gilmour, RAAF

Flight Engineer: Flt. Sgt. Roy Turner, RAF

Instructing Flight Engineer: Flt. Sgt. R. V. Carling, RAF

Wireless Operator: S. O. Jim Potter, RAAF

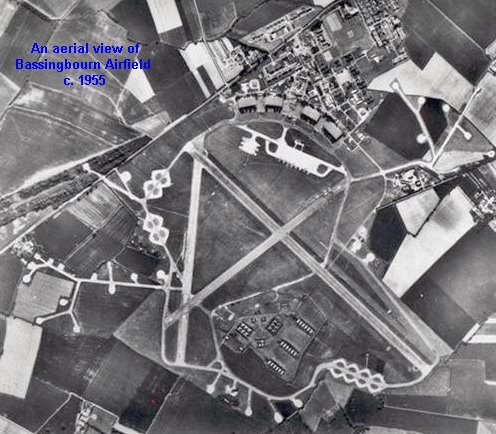

466 Squadron based at Bassingbourn in Hertfordshire were learning how to operate the American B24 as a replacement for their Halifax. The Liberator, the name given by the RAF and later adopted by the Americans, was a powerful four-engined plane designed to be able to sustain a power climb (including takeoff) on just three of her 1,200 H.P. Pratt and Whitney Twin Wasp engines, and to remain controllable using just two (though it must be said, only barely). Her top speed of some 300 mph and long range (the 3,000 miles plus meant she was the first of the big bombers which could be delivered direct from the States to the UK), made her an extremely important weapon in war, and a wonderful workhorse in peace. On September 18th, 1945, a training flight was planned in order to introduce and test the reactions of a mixed British and Australian crew to these emergency engine failure conditions. A three-engined takeoff and landing would be followed by another flight when two engines would be stopped.

It was around 15:00 in the afternoon after a late lunch which had followed the usual takeoffs, circuits and landings as initial familiarization, when the seven crew and a Scottish Terrier puppy climbed back into the refueled KN736, a brand-new Liberator Mk.8 (Flight Lieutenant Spiller's Flight Log Book suggests it was a mark 7A) with (up to that fateful morning) delivery flight hours only, and taxied around to the end of one of Bassingbourn's huge runways, the most famous American air base in Eastern England, home of the B17 Flying Fortresses of the 91st Bomb Group.

The Captain, Flt. Lt. Pat McNulty DFC, RAAF, a veteran of many operational flights in the similar Halifax, was at the controls in the left-hand seat. Under the instruction of Flight Lieutenant John Spiller DFC, RAF, of 59 Squadron from Waterbeach, seconded to 466 Squadron for this training, the flight engineers shut down the starboard outer engine as the wheels left the concrete; the remaining three engines powered the Liberator in her climb in a controlled and safe manner over the fields and lanes, the villages and ponds of East Anglia. Over to the left could be seen another airfield with it's own history: Steeple Morden, home of the American 355th Fighter Group and their P51-D Mustangs.

Pleased with the success of the crew and plane, Flt. Lt. Spiller decided that the other part of the training, handling the plane with just two operational engines, might as well be performed before ending the flight for the day with the three-engined landing. It was a momentous decision. It is possible Spiller felt under pressure of time. Liberators would be required to bring home the troops from the far east, the war with Japan having ended only the previous month. Squadron training had been delayed by bad weather that September, and on this day, the schedule was also running late, so he probably felt it would save time to skip the landing between the two scenarios.

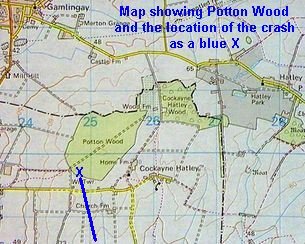

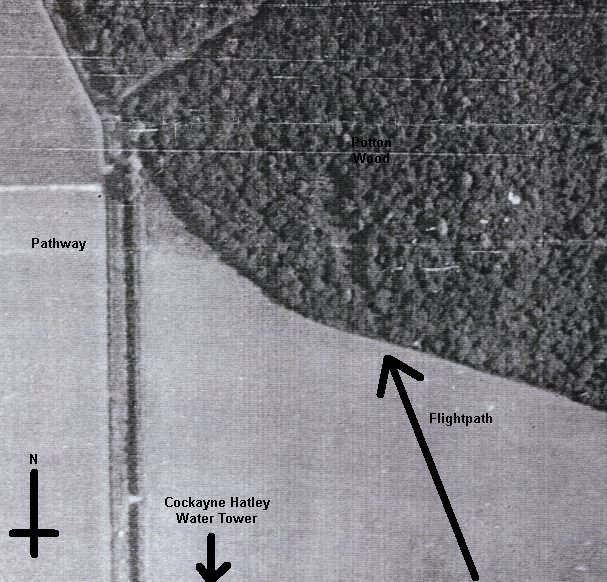

At first, the shut down and feathering of the second, starboard inner engine, went perfectly well, though the effort to maintain straight flight required full left rudder. The aeroplane was losing altitude gradually, and the exercise had started at only 1,200 feet. Any attempt to make a turn to the right would have immediately spun the Liberator into the ground, and the crew discovered there to be insufficient control input remaining to achieve a left turn. Unable to maintain altitude at such a low level, the pilot was flying the plane in an exceptionally risky condition at the limit of control, and as KN736 headed north-west, the land was gently rising towards the Greensand Ridge at Potton; before very long it became essential to restart at least one of the engines.

This was a critical time, as the propeller blades had first to be set to a fine pitch and allowed to 'windmill' to generate the momentum that a starter motor on the ground would have provided; this naturally added drag and slowed the plane significantly at a time when it needed all the speed it could get. The crew performed the tasks required but the engine stubbornly refused to restart, and the plane began to more rapidly lose speed and altitude. Unable to turn and with the ground rising to meet them, the crew were suddenly in deeply serious trouble, with very little time left to sort it out. They hurriedly un-feathered the inner starboard engine, again slowing the plane yet more, but all attempts to restart this engine also failed, and fairly quickly, the starboard wing stalled, KN736 went into a dive and crashed into the southern boundary of Potton Wood. The plane broke into sections and burst into flames.

The aerial image was taken from the official records in 1945, and marked up by myself. These are held at the National Archives at Kew. The Archives record the plane as a type VIII (i.e. 8), but as I have said, Flight Lieutenant Spiller's Log Book clearly records it as a "7A". See the FLICKR link near the bottom of this page. I did contact the NA about the discrepancy, and gave them the link to Spiller's Log Book, but they insist it was a type "8". Perhaps the "7A" was later redesignated as "8".

Whilst some nearby witnesses ran from the scene convinced that there might be bombs aboard (not really likely so long after the cessation of hostilities), at least two local men, Mr. Sam Bonnett and Mr. C. Dennis, stayed and helped the crew in whatever way they could, soon being joined by others from the nearby hamlet of Cockayne Hatley and the local farms. The impact killed three members of the crew outright: Flight Lieutenants Pat McNulty and John Spiller, and Warrant Officer Potter. A fourth airman, Flight Sergeant Turner, called for help but it proved impossible to extricate him until he had suffered severe burns. Taken to the nearby RAF base at Tempsford, his injuries included a fractured skull; the combination with the burns proved too much for the poor man and he died later that evening. The three survivors were all injured, Flight Sergeant R. V. Carling RAF very seriously, and Flying Officer Frank Doak RAAF badly, though he was the only one to 'walk away' from the accident. Section Officer Noel Gilmour, DFC, RAAF suffered broken ribs and ankle and concussion, along with the myriad of cuts, bruises and slight burns that one might expect from such an incident. He regained consciousness in the woods near the edge of the field unsure of how he had extricated himself from the wreckage and surprised to be alive, and with Pat McNulty's puppy 'Bitsa' laying between his legs barking her presence to the rescuers, who had not known of his position for an hour or so after the crash.

The official RAF investigation concluded that pilot error was to blame, a stigma to the reputation of Flt. Lt. Spiller which seems a little unfair today. The direct problem was most definitely the failure of the engines to restart, though the official criticism might also have been aimed at whether it had been wise to stop a second engine without knowing the first could be restarted, or without ensuring adequate altitude to perform the test in case of difficulties in restarting the power plants. Standing orders were for the two-engine test to be started at no lower than 3,000 feet altitude.

Even today, investigators faced with two engines failing (or in this case, not behaving correctly) think individual mechanical failures less likely than a common cause such as fuel problems or human error. It was concluded that the reason the engines failed to restart was due to a failure by the instructor to ensure the fuel mixture controls were changed from 'idle cut-off' to 'rich', an essential part of in-flight engine restart procedures. The engines could never have restarted as they were receiving no fuel. The reason for this failure on the part of an experienced and concientious pilot continues to elude the thoughts of the survivors to this day. There was admittedly a problem with communication, the RAF helmet intercom settings were incompatible to the American system on the newly arrived aircraft, and the crew had great difficulty conversing without it, but both Spiller and McNulty did have special RAF 'Liberator helmets'. Maybe the flight should never have been attempted under such conditions, and the decision to perform the two dead-engine test was considered by the RAF as ill-judged at such a low altitude, but this is all very easy to say in hindsight and safety, and none of it changes the overwhelming sadness of the whole affair.

Little remains today in the woods as evidence of where the tragedy occurred – a few scarred trees which were around at the time and a slight thinning of the woodland now hardly noticeable at all. After the fire, the only remaining identifiable part of the plane was it's distinctive tail section and huge oval side fins; this and the other shattered parts of the wreck were removed by the RAF soon afterwards, and only a scattering of small pieces of debris still remain: I have found a few twisted aluminium plates and brackets and some small sections of Perspex window glass, one showing evidence of the fire. I left them up against a tree in the area.

The two Australian crew who died are interred in the Commonwealth War Graves section of Cambridge Cemetery. Flight Lieutenant Spiller is interred at the Edmonton Cemetery near Enfield. The incident is commemorated on a memorial in Cockayne Hatley's St John the Baptist churchyard, a slab of slate supposedly shaped into the wing tip of a B24, but more likely to my eye, the blade of a propeller, and dedicated in August, 1998.

An image can be viewed at www.flickr.com that has photographs of the crew and other pertinent memorabilia which is very poignant. The image can be enlarged so that all the text is easily readable. The image of the propeller blade (or wing tip) is a clickable link to the Biggleswade Chronicle of 1998 which reported on the memorial's dedication.

The data on this page have been compiled mainly from data supplied by Mr. Stephen McNulty, nephew of the Australian pilot. They include letters from Mr. Noel Gilmour who survived the accident and has first hand knowledge of the events. Unfortunately, I have lost Steve's contact details, so have not been able to follow up how he and Mr. Gilmour are getting on. My last contact was about 1999, at least two computers ago!

|

|

|

|

Flight Lieutenant |

Flight Sergeant |

Wireless Officer |

Flight Lieutenant |